Introduction to Message Brokers

Whenever we have a large enough systems, it’s gets to a point where we need to break it into more than one running component. Nowadays this is often a Web front-end, a set of services in the back-end, and a database.

If we want our services to be able to communicate with each other and pass work around, we need to have the communicate. This communication should be reliable, we want the service to be available as much as possible.

Challenges of Communication

Something isn’t running

One of the problems we have to solve in distributed systems is when something isn’t running when we expect it to be. Having to make sure every component is up and running and ready to take requests at the same time, or all the time, can be difficult.

Having part of our system down often means the whole system is down, or at least everything that depends on it for processing.

What if theres more than 1 running

An almost opposite problem is when we have more that one instance of something running. If we want to be able to have redundancy in our deployments, or if we want to scale our components so they can take more load.

In these instances we have a ‘Service Registry’ problem. How can we get our requests to our service to be fairly balanced across all the running instances, whether theres 1, 2, or 1000.

Dependencies are slow

Another problem we frequently encounter is that not all our components can process work at the same speed. Some services might have quite simple actions to take on their work item, perhaps saving an order to high scale database, while a downstream service prints out receipts/invoices. The printer is going to take longer to process work than a database. How to we enable upstream systems to run at full rate and have downstream systems reliably queue up their work?

Firewalls between components

It might also be possible that our components we want to communicate arent on the same network. There could be network security between them. This is common for external facing components like API services, and our database accessing domain services.

Dont speak the same language

Another problem we can have in heterogenious systems is two components may need to communicate but down speak the same language. They may use different protocols or different data schemas. We want to be able to get in the middle of that communication and be able to do some translation work.

Message Brokers as a Solution

Message brokers can help us solve all these problems for our distributed systems. A Message Broker is an intermediary system that can receive a ‘package’ of data from one party and forward it on to one or more parties. The ability to store these messages between receiving and forwarding them on is the key capability that makes them useful.

Lets look at their features and we can talk about how they solve the above problems for us.

Messages and Queues

A message is a basic unit of data that a one system can send to another through a message broker. It’s normally a chunk of binary data, wrapped in a metadata package.

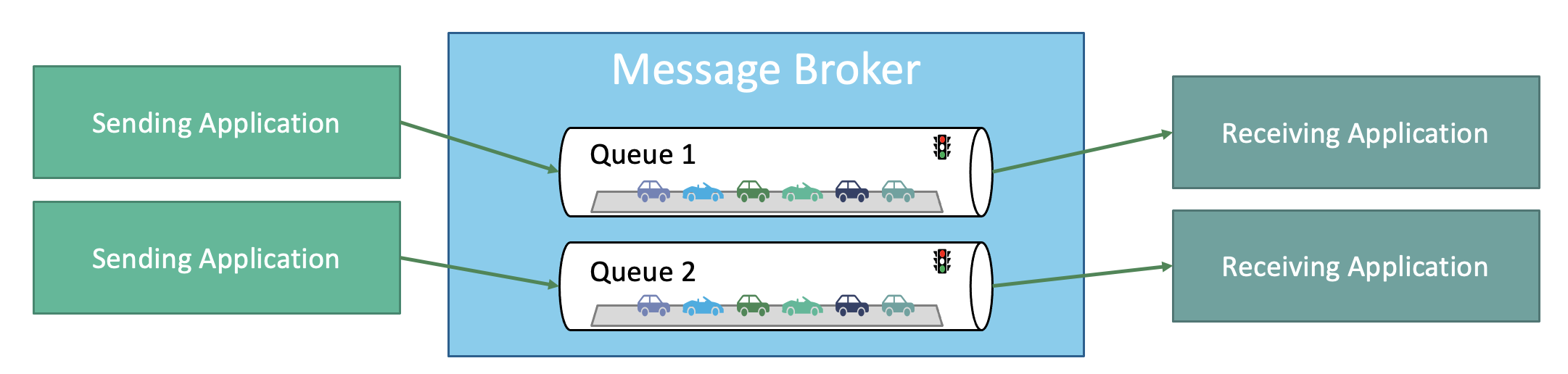

The key piece of metadata about the message is where its being sent to. Now unlike network packages, this isnt the address of the specific system we want to receive it. It the name of a data structure on the message broker where we want the message to be stored. The most basic of these data structures is a Queue

A queue ( like all queues in Computer Science) is a first-in-first-out data structure. It’s basically named list of messages that you read from in the order the messages arrived.

I like to use the analogy of a one lane road. Whatever order the cars enter that road at one end, thats the order they leave at the other end.

Using this analogy we can think of Queues on a message broker as being a set of named streets that we can send out messages (cars) to.

Event at this most basic level, a message broker can help us with our problems.

If the receiving application stops running, the message broker will allow the sending application to still send messages to the Queue. The message broker will then store them up until the receiving application starts again. At that point, it will have access to all the messages that have been sent.

Now this isnt a direct swap of message brokers in place of direct communication. This does require a change to the interaction pattern. With direct communication it would be normal to expect an instant (synchronous) response from the receiver. Your request might be to take an action, or lookup some data. With the message broker in the middle, you dont know for sure that the application on the other end is there. You will need to change the expectation of the sending application.

This naturally also helps us when the receiving application is running slow, thats effectively the same as being down but not quite as bad.

Competing Consumers

Now one of our challenges that we wanted to solve was how to handle more than one instance of a receiving application running. How would we effectively share the incoming communications between the two so they balance the work but dont duplicate the work.

Well, another useful feature of Queues on Message Brokers is the ability to have Competing Consumers. This is the ability for 2 or more receiving applications to connect to a Queue to receive messages. The message brokers will then give each receiver (called a consumer when talking about queues) a unqiue message from the front of the queue.

This means we can scale our consumers as much as we want to do real time paralel processing or just hot standbys, and all of this will be invisible to the sender of the application.

Message Brokers even support allowing messages to be redelived to a new consumer if the first consumer to get the message can’t process it, or fails before finishing it’s processing

Topics and Subscription

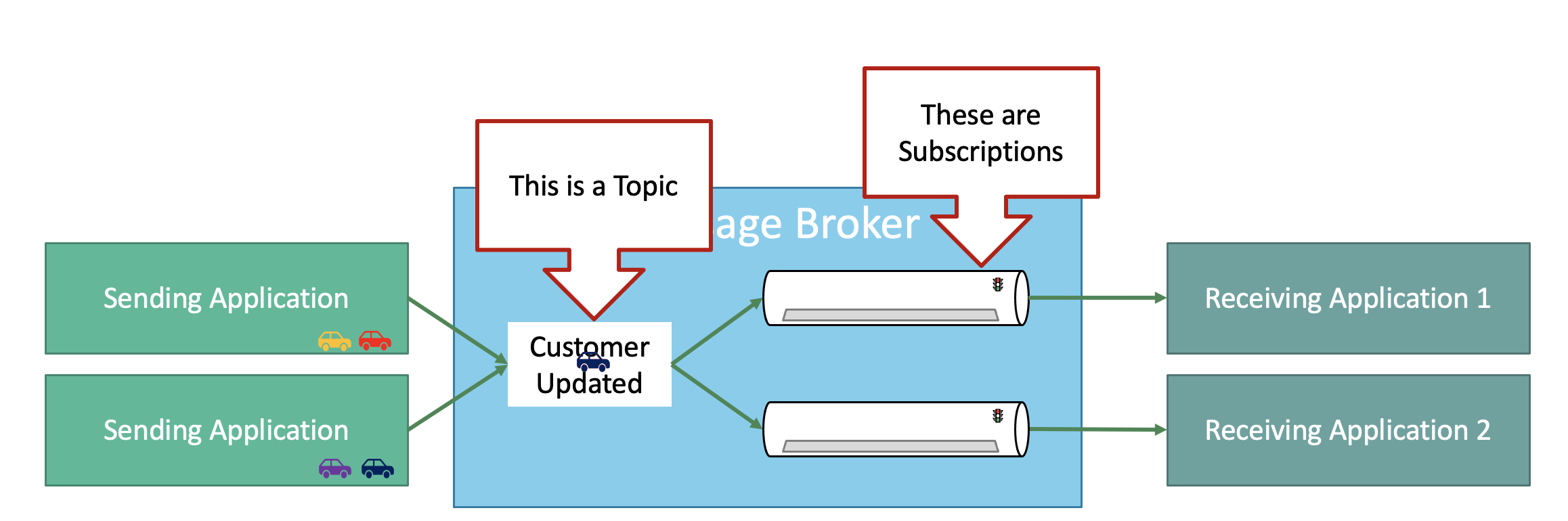

Now Queues are great, but they limited in that a Queue can have lots of Sender/Producers that send messages to it, and lot of Receivers/Consumers which can take messages from it, but each message from a Queue can only be processed by a single consumer.

If you want more than one application to be able to receive a copy of every message, you can achieve that too, by using Topics and Subscriptions.

Topics and Subscriptions work in a very similar fashion to queues. Queues have names that you specify when you send a message to it, that is effectively the same as a Topic. The storage of messages waiting for delivery in a Queue are effectively the same as a Subscription.

So with Topics it’s now possible for a sending application to a send a single Message to the broker, and the broker put that into more than one Subscription (outbound queue) for more than one receiving application to get it. This is often referred to as ‘Fan Out’.

Subscriptions also allow Competing Consumers on them too, so we can scale the number of flows for our messages, and the number of consumers for each flow, without having to specifically build any of that logic into our applications

Downsides

Nothing is ever truly free, and Message brokers are the same. Obviously the first way they aren’t free, is that they arent free. The best either have a licensing cost outright, or are free to use but paid for support. Even if you chose to support a free one yourself, that takes time and time is money.

Secondly, there is the switch from synchronous to asynchronous. This is often a change to the way people think about their systems, and potentially their user experiences. You can’t effectively just swap synch for async in most places, so there is often work to do there, however there are often direct benefits from this too.

Failure detection can also be hard across these systems. Obviously if everything is down then it’s normally quite easy to tell, but if the front-end is up and sending messages, and its just a back end consumer thats not work, it can be harder to tell. For this we often need to put monitoring in place to check that our queues and subscriptions aren’t filling up with messages. We can check the queue size, or the age of the message at the front of the queue. Either way though, we need to be more vigilient as being more tolerant of failure can make failure harder to detect.

Summary

While we’re building ever more complex systems with more moving pieces and potentially across different hosting environments, like on-premise and in the cloud, we are encountering more challenges for communication betwene our components. Message Brokers can be a really useful solution to these problems that provide a lot of features out-of-the-box. They can be fast and simple to setup too, especially when using a cloud hosted Broker like Azure Service Bus.

Like all good things, there are some costs/challenges associated with them, but I think overall they are a great tool for building modern systems.

More Information

I’ve been creating a series of videos on building message driven systems and Azure Service Bus. Check it out here: Building Message Driven Systems Playlist

The source code for the examples in that series can be found in this Github repository https://github.com/ciaranodonnell/AzureDemos/tree/master/AzureServiceBus/

Comments